"Could you tell me where the fridge magnets are?"

That's not a good thing to hear in the gift shop, which you pass through to enter the Royal Academy's brand new blockbustin' show Painting the Modern Garden - Monet to Matisse. But yes, where there is Monet, there are fridge magnets, and scarves, and umbrellas a go-go.

But have no fear, this isn't a fluffy Impressionist marshmallow of a show. This is a show with a big narrative, that of the garden as artistic inspiration from the 1860s to the 1920s, with the emphasis on Monet and his giant outdoor palette of abstract organic inspiration that was Giverny.

Being a member of the RA, I was lucky enough to be able to go to both the evening preview and spend the next day at the show before it opened to the public. The show opens with a room called 'Impressionist Gardens', presenting Monet as both gardener and artist. (This was quite interesting, as Lachlan Goudie made the point in The Story of Scottish Art that painters weren't merely painters during the Scottish Enlightenment, they were also engineers and architects and so on. An 18th century painter was therefore far more educationally rounded and well-read than art students today who just paint. Which made me feel quite chuffed at my own career path...)

So let me take you on a walk through the rooms of the exhibition.

Greater affluence and leisure time in the 1800s (for certain sections of society) led to a boom in gardening, with exotic new plant species being brought back from far flung places. Artists began to treat their gardens as outdoor studios (at least in France where the weather is better). This was nature tamed - sensory, textural, patterned.

Greater affluence and leisure time in the 1800s (for certain sections of society) led to a boom in gardening, with exotic new plant species being brought back from far flung places. Artists began to treat their gardens as outdoor studios (at least in France where the weather is better). This was nature tamed - sensory, textural, patterned.

Interestingly for landscape paintings, many of the ones in the exhibition are on a portrait axis, as is this one by Monet, The Artist's Garden at Vetheuil (1881)

Or this from Room 3, Gustave Caillebotte's Nasturtiums (1892) .

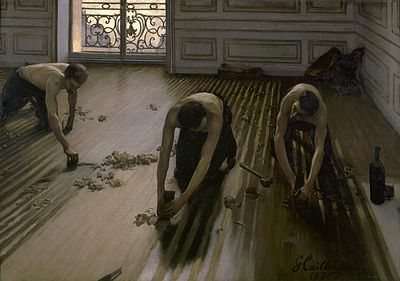

Now, I thought this was very very beautiful, but 'RA Friend's Guest' thought that it looked like wallpaper. M. Caillebotte's earlier work is perhaps not so colourful or abstract, but has similar pattern-making qualities, as seen in this, Les Raboteurs des Parquet of 1875, where three men scrape the varnish on Caillebotte's studio floor in a quietly homoerotic way.

Room 3 is International Gardens, with Joaquin Sorolla (Continental Europe) and Childe Hassam (America). Here's Sorolla painting Louis Comfort Tiffany in 1911 on a grand scale.

There is also Monet's Chrysanthemums of 1897, reminiscent of his later waterlilies - no horizon, pattern-making, decorative, like pastel fireworks, and showcasing the new varieties of flowers.

Room 4 introduces Monet's Early Years at Giverny. In 1883, Monet, who had made his fortune as a successful artist, bought a house at Giverny near Paris, and set about redesigning the gardens including lily ponds based on the ones seen at the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition. He purchased land across the road from the house and diverted a local river (much to the initial objection of locals) to create ponds in 1893. These he filled with new types of waterlily - reds and pinks - a weeping willow, and a bridge inspired by Japanese woodcuts.

Monet built huge studios, glasshouses, and had a staff of at least six gardeners, who had thousands of plants, trees and flowers brought in to be cultivated and tended. He was building a hugely ambitious outdoor painting laboratory, which must have cost an absolute fortune, and gives you some idea of the wealth and level of fame that Monet had created from being a painter.

(It should be noted that the exhibition does present a very particular narrative of 19th century art history, with an eye to the RA target audience. Whilst all exhibitions naturally must follow a particular theme, here the idea that artists of this time were all men who were out in their huge leisurely gardens, painting in the summer sun and responding to nature, is a narrative that is very much of a particular social class, gender and geographical location where there is such a thing as summer sun. Monet would never have had the financial resources to own and maintain Giverny, and to paint his vast experimental canvasses of waterlilies, if he hadn't been propelled to earlier fame and monetary success by the creativity of his dealer, Durand-Ruel. Impoverished contemporary Chaim Soutine, for example, could only afford to buy a couple of buckets of blood from the local butcher to slosh about the still life in his garret, not buy up tracts of land to paint pretty flowers. But I don't think Soutine's Carcass of Beef is ever going to make it onto a fridge magnet...)

Having said all that, here is a map of Giverny (on show in the exhibition along with various letters and documents), with the huge house at the top, the studios and glasshouses to the left and right, and across the road at the bottom are the lily ponds.

Monet built huge studios, glasshouses, and had a staff of at least six gardeners, who had thousands of plants, trees and flowers brought in to be cultivated and tended. He was building a hugely ambitious outdoor painting laboratory, which must have cost an absolute fortune, and gives you some idea of the wealth and level of fame that Monet had created from being a painter.

(It should be noted that the exhibition does present a very particular narrative of 19th century art history, with an eye to the RA target audience. Whilst all exhibitions naturally must follow a particular theme, here the idea that artists of this time were all men who were out in their huge leisurely gardens, painting in the summer sun and responding to nature, is a narrative that is very much of a particular social class, gender and geographical location where there is such a thing as summer sun. Monet would never have had the financial resources to own and maintain Giverny, and to paint his vast experimental canvasses of waterlilies, if he hadn't been propelled to earlier fame and monetary success by the creativity of his dealer, Durand-Ruel. Impoverished contemporary Chaim Soutine, for example, could only afford to buy a couple of buckets of blood from the local butcher to slosh about the still life in his garret, not buy up tracts of land to paint pretty flowers. But I don't think Soutine's Carcass of Beef is ever going to make it onto a fridge magnet...)

Chaim Soutine, Carcass of Beef 1925.

Not fridge magnet material, more Guantanamo Bay.

Having said all that, here is a map of Giverny (on show in the exhibition along with various letters and documents), with the huge house at the top, the studios and glasshouses to the left and right, and across the road at the bottom are the lily ponds.

In 1902, aged 62, Monet produced a series of large paintings in which he focussed entirely on the surface of the water, to the exclusion of the horizon, looking at subtle shifts of colour, light and atmosphere in the reflections.

In 1909, 48 of the paintings were exhibited with Monet's dealer Durand-Ruel under the title Water Lilies: Series of Water Landscapes. Critics praised their timelessness and modernity - "No more earth, no more sky, no limits now" - although Monet himself had found the project so difficult that he had destroyed a number of canvasses.

Room 6 is 'Gardens of Silence', where nature is 'devoid of human presence.' However, although there are no figures in the paintings, human presence is everywhere in the taming, controlling and formalising of nature - as can be seen very well in this glowing painting by Santiago Rusinol Glorieta Aranjuez of 1919.

It may be superficially ultra-orderly, but Rusinol's garden has a strange tension and agitation to it amongst the opulent, sensually heady profusion, such as is found in his equally sensual and heady, sheet-gripping La Morfina of 1894.

Now we come to Room 7, and I'm sorry, but I just can't forgive the title of this room. Avant Gardens. Stop it.

The room contains Klee (one tenth of his paintings contain plant imagery), pattern-making Klimt, jolly Kandinsky

Matisse (oh dear), the emotional intensity of Nolde's rough canvas, and the essential energy of Van Gogh's writhing nature.

Kandinsky, Murnau, the Garden II (1910)

Matisse (oh dear), the emotional intensity of Nolde's rough canvas, and the essential energy of Van Gogh's writhing nature.

Room 8 is Gardens and Reverie, which is all about the Utopian visions of the Symbolists and the Nabis (which didn't do anything for me), and Room 9 presented a huge film of Monet in action of the banks of his lily pond, along with grainy photos of any 19th century artist who had ever been snapped in a garden. Extraordinarily, one was even a woman (Morisot)! Because women don't get a look-in in this show. They obviously hadn't braved it outside into the garden in the 1800s, poor things.

Room 10 switches the narrative back to Monet, and his Later Years at Giverny. Devastated by the death of his wife Alice, Monet didn't paint at all from 1911-14, and his eyesight was poor. However, things improved in 1914, and he turned again to the theme of waterlilies, obsessively developing the theme until his death in 1926.

Here is his Japanese Bridge in 1899

and here it is again in 1923, writhing and flickering abstractedly on the canvas like a piece of late Titian.

Here is his Japanese Bridge in 1899

and here it is again in 1923, writhing and flickering abstractedly on the canvas like a piece of late Titian.

Yes, Monet was now seeing the bridge through cataracts, but he was also painting with the sort of don't-give-a-toss freedom that old age and the familiarity with both your subject and your materials gives. Just think of his other series paintings, such as Haystacks

or Rouen Cathedral

where the subject melts ecstatically into the mark-making. The paint itself and the sense of the object becomes more important than the mere depiction of the object.

"The subject is secondary. What I want to reproduce is that which is between the subject and me."

These last rooms are undoubtedly the best in the exhibition. Here are enormous 6 foot by 7 foot canvasses, covered in textural mark-making. Waterlilies bloom in late July and August, so the paintings are done under hot French summer sun in the garden, and the dry, scumbled nature of the paintmark pays testament to the conditions under which they were made.

Monet Waterlilies (1914)

Of course the years of 1914-18 were the First World War. Monet refused to leave Giverny. The guide to this show notes that 'the sombre deep blue and violet tones in some of his waterlily paintings, and particularly the motif of the weeping willow...seemed to express his distress at the tragedy of the war." Er, really?

Or it could have just been that the weather made dark skies and dark reflections, and that he had a weeping willow in his garden already which had been there since 1893 (you can see it on the top edge of the ponds in the plan). Did he plant a specific tree in order to anticipate global warfare by a decade, or did he plant a tree naturally found by rivers in order to create interesting striped compositional patterns on the surface of the water...?

Perhaps the allusion to external landscape as inner landscape is referring to this - Ice Floes on the Seine of 1880.

Firstly, it's a precursor of the waterlily paintings (except it is still compositionally conventional in that you can see the horizon - the waterlily paintings turn right down to focus on the water surface for all the action).

Secondly, I was told in my Fine Art lectures that the desolate subject expressed Monet's inner grief at the death of his first wife. Which is a fine analogy - ice floes = intense grief at death of spouse.

However, Monet painted ice floes over several winters whenever they appeared on the Seine, not just at the death of his wife. He liked the subject. And at the time of Camille's death, Monet was in a relationship with Alice, the wife of his best friend, whom he moved in with not long after painting the tragic ice floes above.

So what I'm saying is - imposing meaning on art is a minefield. You don't know all the facts. Sometimes life is a lot more complicated, and sometimes art is a lot more simple.

And on to the final room of the show - the vast triptych of Waterlilies (Agapanthus) of 1915. Each canvas is 7 foot high and 14 foot wide, so the woeful little illustration below in no way conveys how cathedral-like and immersive the work is.

Monet had envisaged a number of monumental projects - continuous panoramas of canvasses, panels forming circular 360 degree compositions, which were to be (according to the panels of information in the room) about war and peace, trauma and harmony, beauty and ugliness, joy and sorrow and life and death. But no agapanthus. They got the chop in the final composition. So just waterlilies.

For various reasons, this megaproject never came to fruition, but three massive panels did. To complete them, Monet increasingly painted in his studio from memory, guided by his own inner notes and observations of the subject, and the relationship and dialogue which oscillated between the canvasses themselves as he worked on them. The canvasses themselves started to dictate what the painting was, and he listened to what they had to say and interpreted that. As an artist, I can understand that completely.

They remained in his studio after his death until the 1950s, when the family sold them to 3 separate American museums. In this exhibition, they are reunited once again.

And so the dry, layered paint oscillates and resolves, and the flickering brushwork advances and recedes, like the facade of Rouen Cathedral dissolving in the sunlight, or the 50, 60, 70 layers of glazes on a late Titian. Old artists never retire. Old musicians might end up writing toothless marshmallow twaddle in their dotage, but old artists gain an extra edge with advancing years - a fearlessness and disregard for convention that combines with a complete knowledge of their materials and a muscle memory for mixing colour.

And here it is laid out in this final room, Monet fearlessly going bigger, grander, more abstract than ever before. Good for you, M. Monet.

Excellent review and summing up. I've just been to the exhibition this morning and was struck by the brilliance of Monet (100 years ahead of everyone else) and the banality of some of the 'interpretations'. Funnily enough, I was also baffled by the notes about Monet and war, and i had to do a double-take when I saw 'Avant Gardens'. Still, wonderful to see so many Monets in one place.

ReplyDeleteHi Jane

ReplyDeleteLovely to hear from you and get your feedback - thank you for your kind comments about my review!

Great to hear that you had such a positive experience of the show. In the late works, Monet does indeed almost pre-empt abstract artists such as Pollock, with his fearless use of paint, dribbled and squiggled and dragged across the surface of the canvas, so that is almost entirely (but not completely) released from the depiction of the object.

And yes, it's a real treat to see so many Monets in one place!

Extraordinary creativity Harmony Makeup Studio made me look amazing for my wedding day. I highly endorse their competent services.

ReplyDeleteHarmony Makeup Studio